This century-old idea could save 10 million lives a year by 2050

24 Oct 2017 | Lydia Ramsey

Phage therapy is used to treat infections that become resistant to drugs, and was discovered in the 1900's

Antibiotic resistance — the phenomenon in which bacteria stop responding to certain antibiotics — is a growing threat around the world.

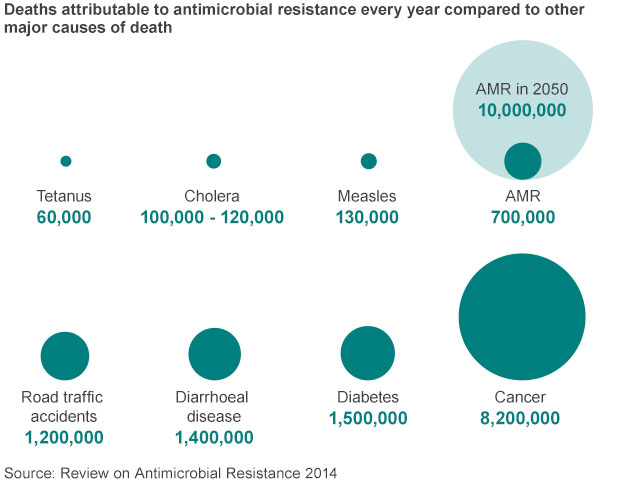

It's expected to kill 10 million people annually by 2050.

And it hasn't been easy to develop new drugs in order to stay ahead of the problem. Many major pharmaceutical companies have stopped developing new antibiotics, and the drugs that are still in development have faced numerous stumbling blocks toward approval.

So some drugmakers are starting to turn to other solutions, including one that's actually had a fairly long history: phage therapy.

Have you read?

- How can we create a healthier world?

- Healthcare in 2030: goodbye hospital, hello home-spital

- What will healthcare look like in 2030?

The treatments are made of bacteria-killing viruses called bacteriophages, or phages for short. Discovered in the early 1900s, bacteriophages have the potential to treat people with bacterial infections.

They're commonly used in parts of eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union as another way to treat infections that could otherwise be treated by antibiotics. Because they are programmed to fight bacteria, phages don't pose much of a threat to human safety on a larger scale.

"There's huge potential there that regular antibiotics don't have," NYT columnist Carl Zimmer told Business Insider in 2015. "I think what we'd actually have to work on is how we approve medical treatments to make room for viruses that kill bacteria."

A conversation about approval pathways is already underway, with a handful of companies starting to get into the space. The trials, while still in early stages, could one day change the way we confront antibiotic resistance.

A need for new options

Dr. Paul Grint, CEO of one small company, AmpliPhi Biosciences, is trying to turn phage therapy into a tool that doctors might be able to one day use alongside antibiotics to treat serious infections. The company's working on phage-based treatments to treat Staphylococcus aureus, a bug implicated in sinus infections, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bug connected to lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis.

There are a number of reasons why these treatments are gaining some momentum now: for one, there's a big need for antibiotics. In September, the World Health Organization warned that the world is running out of antibiotics.

"There is an urgent need for more investment in research and development for antibiotic-resistant infections including TB, otherwise we will be forced back to a time when people feared common infections and risked their lives from minor surgery," WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a news release.

For phages in particular, there have been a number of advancements that help make it more straightforward for phage therapy to go through the FDA approval process. Grint told Business Insider that includes being able to sequence the bugs, which would help determine that you're absolutely getting the right phages in treatment.

AmpliPhi also has a way to manufacture the therapy that's up to regulatory standards set up by the FDA.

Using phage therapy in the US

While phage therapy has been around for more than a century, Grint said there's still a lot of education that needs to happen to get doctors and researchers on board, especially in the US. In July, the FDA and National Institutes of Health hosted a workshop regarding bacteriophages, which Ampliphi and others participated in.

There are also some researchers like a group at the University of California at San Diego that are researching phage therapy. In 2016, for example, researchers at UCSD used AmpliPhi's therapy to treat a professor at the university who had a drug-resistant infection.

Even so, the US is treading carefully into the world of phage therapy. For now, AmpliPhi is able to recruit patients under the FDA's "compassionate use" pathway, making it mostly a case-by-case situation for now when other antibiotics have failed.

The hope is to use that information, along with some phase 1 studies that are happening in Australia to gear up for a phase 2 trial in the US. The company's aiming to start that trial in the second half of 2018, meaning it still might be a while before we start using viruses to treat our bacterial infections.

How Businesses Can Drive Health Care to the Underserved

More than a billion people worldwide, including in the U.S., lack access to basic health care, but they are very much on the radar of some public spirited organizations, both big and small.

A Crowd Is Waiting For A Cervical Cancer Clinic On Wheels

Women wait by a maternal health care clinic in Pabre, Burkina Faso, for a free cervical cancer screening. Matthea Roemer for NPR